Josh Voyles and his RAW shirt.

image © 2012 Samuel Morse

Ever wonder what “14-bit RAW recording” or “24-bit audio” really mean? Hopefully this will help clear some things up.

Bit depth, or the number of bits used to define a pixel’s color or an audio sample’s amplitude, is an indicator of image or audio fidelity. A bit is one digit in binary code, a one or a zero. For instance, 16-bit audio has 16 ones or zeros to define amplitude. I say that this is an “indicator” of fidelity, because a high quality analog-to-digital converter (ADC) is required to accurately translate the analog world into ones and zeros.

Each additional bit doubles the possible number of combinations or values. Two bits has four possible values (00, 01, 10, 11), and three bits has eight. Coincidentally, this is how you can count to 32 on a single hand, using your fingers as binary digits rather than a cumulative total. Here are some more examples of what a number of bits equates to in terms of possible values. I’ve color-coded the values to make them easier to read.

8-bit: 256 possible values

16-bit: 65,536 possible values

24-bit: 16,777,216 possible values

As a side note for audio, this only refers to how accurately the anologue to digital converter can measure amplitude, the other half of the quality is in Hz, or the frequency in which the amplitude is measured, e.g., a 24-bit 192 kHz signal is sampled 192,000 times per second using 24 ones and zeros to measure amplitude in each sample.

In digital images, a listing of bits generally refers to bits per channel, rather than the total number of bits that define a color value for a given pixel. For an RGB file like most digital camera files, the number of bits is tripled, defining values for each channel; red, green, and blue. A standard JPEG file has 8 bits per channel, so that means a total of 24 bits to define each pixel’s color. Here are the number of possible values for the most common bit-depths.

8-bit (jpeg): 16,777,216 possible colors

12-bit (standard RAW file): 68,719,476,736 possible colors

14-bit (high-end RAW file): 4,398,046,511,104 possible colors

16-bit (TIFF or medium format RAW file): 281,474,976,710,656 possible colors

What does this mean for image quality? Well, most devices can’t handle more than 8 bits per channel, so a lot of that data is lost no matter what you do. What a higher bit depth really helps with is editing. This is particularly true with the expanded dynamic range of modern digital cameras. Let’s see if I can explain this without loosing people.

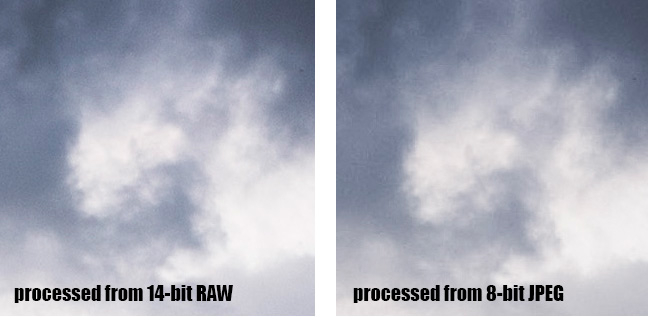

Say you have a landscape image you shot in RAW (14-bit). The dynamic range is immense because you have bright sky and dark shadows in the image. You decide apply a graduated filter effect, darkening the sky to bring back full detail there, and increasing the contrast to give it a lot of “punch.” For that sky, the detail was only recorded in the top 10-20% of the original file’s histogram (i.e. brightness values), but you’re now shifting those values to cover 40-60% of the resulting JPEG’s histogram. This means you’ve spread those values out 4-6 times their original area on the histogram. If you were editing from an 8-bit file, this would leave gaps in the histogram and harsh edges where color tones mix. However, with a 14-bit file, there are 64 intermediary values to chose from, so tones remain smooth.

I did my best to illustrate this concept below. I used a raw file I had processed, created a duplicate image as if it was a low contrast JPEG straight from the camera, and tried to apply the same settings to the resulting JPEG. Mind you, if you don’t think there’s that much of a difference, this still requires you to turn down the contrast on your camera significantly to get these sort of results. This image is heavily processed.

Here’s the full res file, followed by the 100% crop:

And people wonder why I shoot RAW…